What makes a planet?

2015 update

The IAU definition of 'planet' needs improvement because it is

neither quantitative nor general. I proposed a simple criterion that

can be used to quantify, generalize, and simplify the definition.

This criterion makes it possible to immediately classify 99% of all

known exoplanets. All 8 planets and all classifiable exoplanets

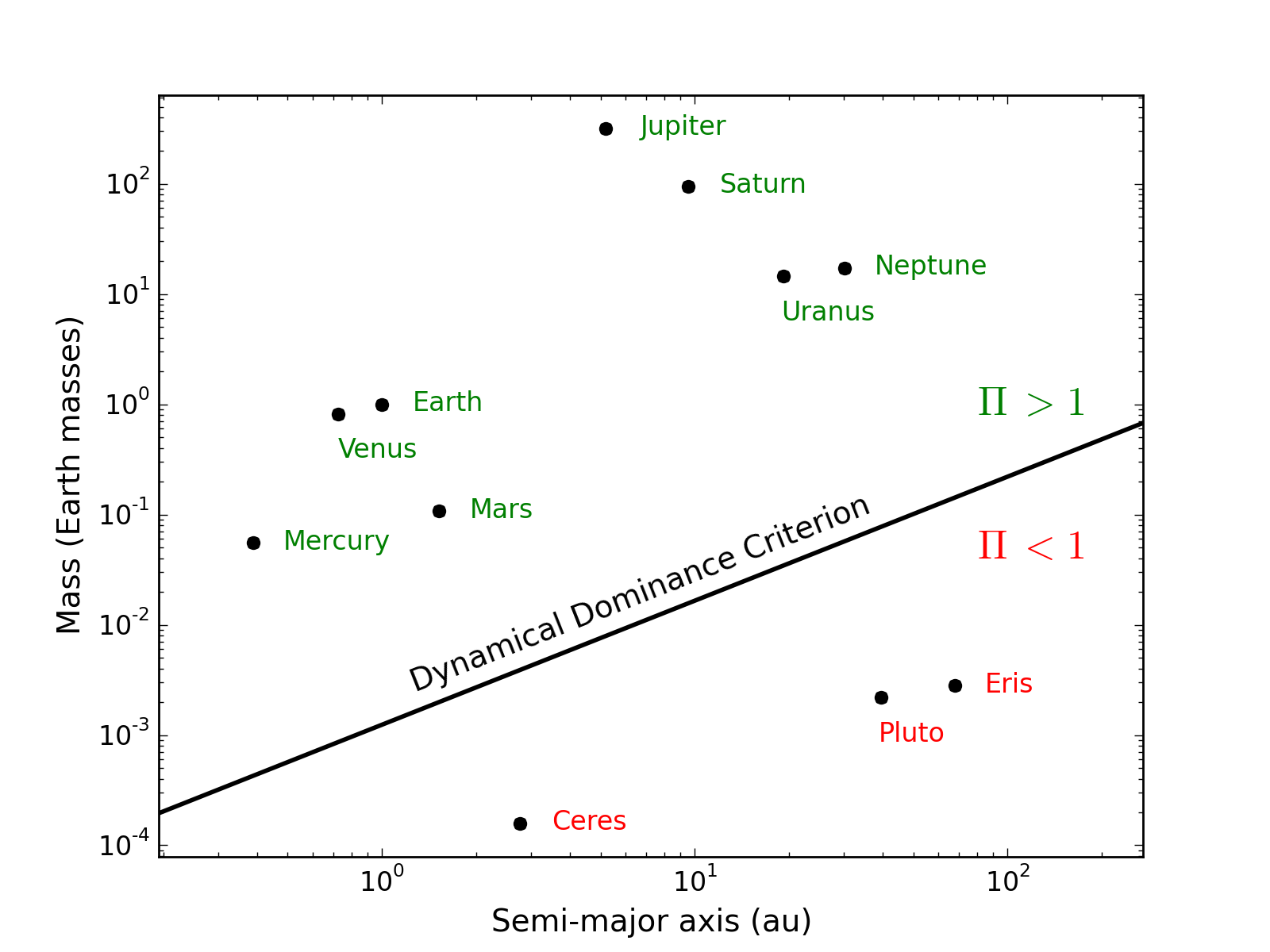

satisfy the criterion. The figure below shows the criterion applied

to the solar system (objects above the bold line are

planets according to this criterion):

Planet test applied to objects in the solar system. All 8 planets have a mass that exceeds the mass required to dynamically dominate the corresponding orbital zone.

You can download a poster that describes the proposed definition. The article describing the criterion is published in the Astronomical Journal and is available online.

Planet Definition

In 2006 we developed and implemented an official classification of the celestial bodies in our solar system. There are 8 planets, a small number of dwarf planets, and a large number of minor planets. The decisive criterion in the definition of a planet is based on dynamics (i.e. the science of forces and motions). This is an intelligent decision, and a decision that we can feel good about, for several reasons:

- Planets have always been defined by their dynamics. The word "planets" comes from the Greek word for "wanderer", an object that moves across the background of the fixed stars.

- Moons have always been defined by their dynamics. A moon is an object that moves around (orbits) a planet. There are moons that look round and there are moons that don't look round at all. Their shape is irrelevant to the moon classification.

- A classification based on dynamics is far easier to implement than a classification based on physical properties. Newly discovered objects can be classified immediately, long before the details of their physical properties are known.

- We already classify other objects in our solar system based on their dynamics, such as the near-Earth asteroids (Aten-Apollo-Amor), the Trojan asteroids, the Centaurs, the trans-Neptunian objects (resonant-scattered-classical).

Many branches of science require a precise classification scheme (a taxonomy), otherwise people cannot talk to each other effectively. Astronomy is no different. A precise definition for the word "planet" was needed.

Who decided?

Scientists did. Just like scientists defined "triangle", "energy", or "acid". Most people agree that it's a good idea to let biologists provide the definition for "bacteria" and "viruses". Scientists provide precise definitions for scientific terms as part of their job.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) is an organization of over 12,000 professional astronomers. It is the only community of experts that has the legal and scientific authority to define the word "planet". The IAU has been in charge of planetary nomenclature since 1919. It holds a General Assembly every three years, and the 2006 meeting was held in Prague, Czech Republic.

Why the urgency in 2006?

Two very important developments in our knowledge of "planetary systems" occurred in the 90s: the discovery of celestial bodies orbiting stars other than the sun, and the discovery of a vast belt of small bodies orbiting the sun beyond Neptune. Both of these developments made it pressing to arrive at a proper definition for the word "planet". People were making claims of discovering new planets, but were they really planets? The taxonomy as of 2006 was incomplete, and there was a very strong sense that the IAU needed to define a planet at its 2006 General Assembly.

What happened when Pluto was discovered?

In 1930 staff at the Lowell Observatory issued a circular entitled "Discovery of a solar system body apparently trans-neptunian" for distribution to astronomers around the world. The announcement describes a new "object" and makes no claim of a planet discovery (see the full text from the Lowell Observatory archives here). This object later became known as Pluto.

The term "trans-Neptunian" (literally "beyond Neptune") is used today to represent a very large number of objects that orbit the Sun beyond the orbit of Neptune. This population is also referred to as the Kuiper belt or Edgeworth-Kuiper belt.

What changed between 1930 and 2006?

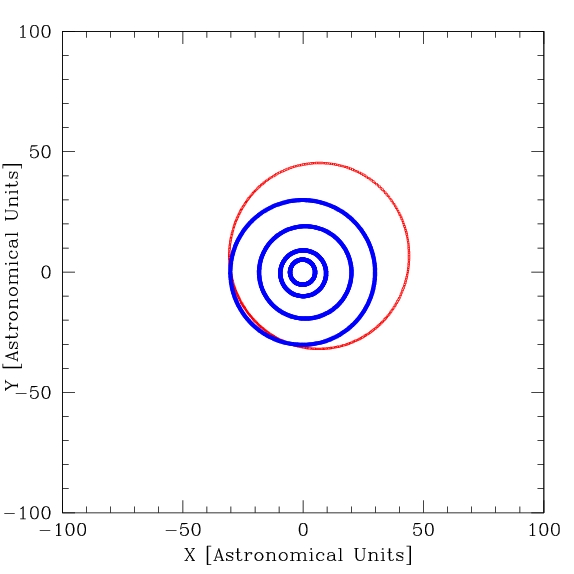

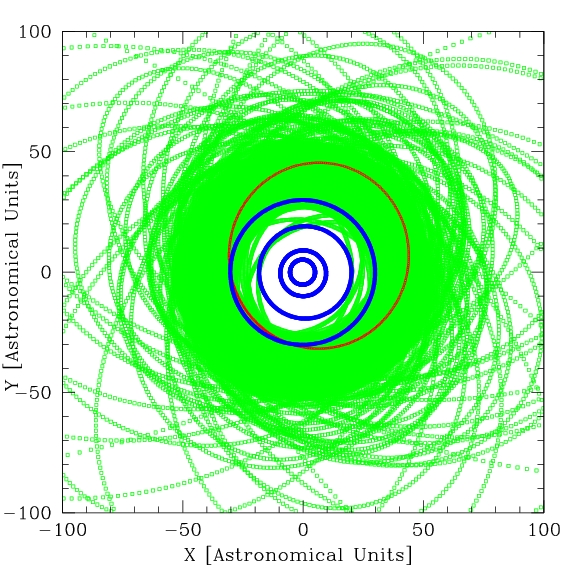

New discoveries! The two figures below show the trajectory of objects

in the plane of the solar system (the sun is at the center, but it is

not shown). The figures compare our knowledge at the time of Pluto's

discovery and our knowledge in 2006. The orbits of the four Jovian

planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) are drawn in blue, the

orbit of Pluto in red, and the orbit of about 800 of Pluto's friends

in green. Based on these diagrams one can understand how astronomers

in 1930 felt that Pluto was an exceptional object and decided to call

it a planet. One can also easily understand how the vast majority of

astronomers in 2006 recognized Pluto as a large member of a population

of small bodies beyond Neptune. If Pluto were discovered today in the

midst of all its friends, few people would even suggest

considering it as a planet.

Two figures contrasting our knowledge at the time of Pluto's discovery and our knowledge in 2006.

Why is Pluto no longer a planet?

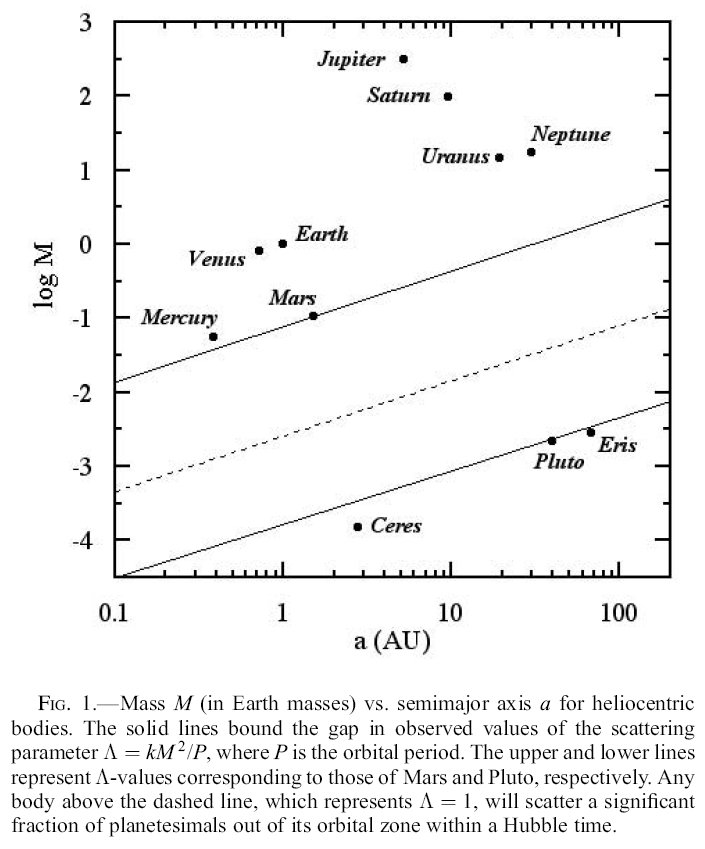

One of the best illustrations of the fact that Pluto is a very different

animal from the eight planets was published by Steven Soter in the

Astronomical Journal in 2006. The figure clearly shows that some

bodies are capable of clearing their orbit, whereas other bodies are

not. (This orbit-clearing criterion is what the IAU decided to use in

its definition of a planet. It's a criterion based on dynamics and

not geophysics.)

There is a fundamental difference between the planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) and Pluto. This difference explains why Pluto is not classified as a planet. Unlike any of the planets, Pluto is embedded in a vast swarm of bodies similar to itself. Pluto is therefore analogous to the asteroid Ceres in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Pluto has many friends orbiting nearby, which is not the case for any of the planets. The planets accumulate, eject, or otherwise control all the mass in their immediate proximity. Pluto and Ceres are not able to do that; therefore they belong to a class that is really quite distinct from the eight planets.

Some who argued for maintaining Pluto as a planet proposed the following arguments:

- Pluto has a tiny atmosphere. Several moons of the Jovian planets have an atmosphere, so the presence of an atmosphere is not a distinctive feature of planets.

- Pluto has satellites. Many small asteroids and trans-Neptunian objects have satellites, so the presence of a satellite is not a distinctive feature of planets.

- Pluto is round. Many moons are round and some asteroids are round, so roundness is not a distinctive feature of planets.

Pluto is no longer a planet!

That's ok. Science is all about recognizing that earlier ideas may have been wrong. For a long time biologists thought that all microbes causing diseases in humans were bacteria. At some point scientists realized that there was another class of microbe more properly described as viruses, and they had to change their ideas about which infective agent was what. We are all better off now as the new classification has clarified meaning and has allowed researchers and health professionals to communicate with each other and the public. Astronomers had to revise their classification in light of our improved understanding of the solar system. Pluto is now recognized as a large member of the trans-Neptunian population.

Did the decision cause a cultural revolution?

It caused a storm in a teapot. Pluto was considered a planet for only 75 years, and questions about its planetary status had been raised for more than 10 years. Compare that to the thousands of years during which schoolchildren were taught that planets revolved around the Earth. When scientists demonstrated that planets revolve around the Sun, people had to make very serious adjustments to their ways of thinking. But people adjusted. And they also adjusted quite well to a solar system with eight planets. Some people resisted. People are resistant to change, and this resistance is sometimes obvious in discussions involving Pluto. Most non-scientists understand the arguments quite well and have no problems with the current classification of planetary bodies.

What about the mnemonic?

New mnemonics are easy to make. Try it, it's fun! Here are some examples:

My Very Eclectic Mother Just Served Us Nabokov

My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Newton

My Very Egotistical Mother Just Served Us Nothing

My Very Egregious Mother Just Served Us Nicotine

My Very Emotional Mother Just Served Us Nostalgia

My Very Empty Mother Just Served Us Nihilism

My Very Energetic Mother Just Served Us Nitroglycerin

My Very European Mother Just Served Us Nutella

My Very Excellent Mother Just Served Us Nectarines

Who is unhappy with the decision?

A very small number of astronomers have been opposing the classification quite vocally. Some of them have said that they prefer a classification based on geophysics and not dynamics. However the language that they are using ("Save Pluto") reveals an emotional attachment to Pluto. According to the geophysics proposal, the large asteroid Ceres would also be counted as a planet, but the people who became so upset about Pluto in 2006 had done absolutely nothing to try to "Save Ceres" prior to 2006 (Ceres was considered a planet in the first half of the nineteenth century, and was demoted from its planetary status when new discoveries showed that it had many friends orbiting nearby - just like Pluto). This inconsistency in behavior suggests (but does not prove) that the objection to Pluto's demotion has more to do with attachment to Pluto than it has to do with geophysics.

How did the IAU arrive at its decision?

On Aug 24, 2006, the assembly of IAU members voted

overwhelmingly in favor of a resolution that defines three

distinct classes of objects in the solar system: planets, dwarf

planets, and small solar-system bodies. (The majority was so

overwhelming that a count of the votes was unnecessary). There are 8

planets in the solar system: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter,

Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. A dwarf planet is not a planet, just

like minor planets are not planets (A resolution that would have

allowed dwarf planets to fall under the umbrella of planets was

strongly defeated by the assembly). Here is the full text of the

resolution that defines a planet in the solar system.

Is the language of the resolution perfect?

It is not. In an attempt to draft a resolution that was jargon-free and understandable to the public, some scientific rigor was lost. In particular, the language "clearing its orbit" implies that a planet is the dominant body in its neighborhood and gravitationally controls its neighborhood. Some people who are unhappy about the planet definition have claimed that Jupiter or Neptune have not "cleared their orbits", which is an obvious misrepresentation because these bodies clearly dominate their orbital zones.

The IAU definition is also imperfect in that it applies only to the solar system. At some point, we will need to revisit the issue in order to establish a classification scheme for exoplanets as well. (Update: here is an easy way to do it).

Other factors contributed to imperfect language. The "Planet Definition Committee" chose to work in secret, very much at odds with fundamental scientific values of transparency and openness. They also released their proposal to the press prior to releasing it to their fellow scientists for review. The avowed intent was to create a "media blast" that would quell all further discussion. This approach did not work, because the proposal was so awkward that IAU members refused to approve it and instead demanded a change. There was little time to craft, review, and agree on new language before the end of the meeting, in part because people were busy attending scientific sessions. Although imperfect, the resolution ultimately adopted by the IAU is a considerable improvement over the initial proposal. A lot of the criticism leveled against the IAU (unfairly, in my opinion) could have been avoided if the Planet Definition Committee had been more transparent.

Should we be concerned about the voting process?

The resolution was passed by an overwhelming majority of those in attendance, following the protocol in place for all IAU resolutions. As polling experts will tell you, polling the IAU assembly (over 400 present) captured the desire of the entire IAU membership (about 9,000 members at the time) with a confidence interval better than 5%. Because the meeting had many scientific sessions, including sessions on the physical properties of asteroids, it was well attended by geophysicists and dynamicists alike, and there is no reason to believe that the voters did not form a representative sample of the entire IAU membership. The schedule for the discussions and vote had been well advertised. Any IAU member who had an interest in this issue was welcome to participate in the discussions and vote.

Is science done by a vote?

Some opponents of the decision have expressed the opinion that scientific matters are not resolved by a vote. Although most scientific activities are not conducted by vote, there is nothing unusual about agreeing to scientific conventions and taxonomic systems by vote. For instance, the set of recommended fundamental physical constants is regularly reviewed and approved by vote. The location of Earth's prime meridian was decided by vote. New mineral names and new asteroid names are approved by vote. The International Commission on Stratigraphy defines the geologic time scale by vote. The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature is regularly revised and approved by vote. When it comes to agreeing to scientific conventions or taxonomic systems, voting by a panel of experts is the best process at our disposal.

What about the petition?

Some people who were unhappy about the outcome of the vote organized a petition to protest the decision by the IAU. The petition was a colossal failure. Even though the organizers of the petition had access to over 9,000 IAU members, only 79 IAU members signed it, some people with no formal astronomy training signed it, and none of the members of the Planet Definition Committee signed it. Among the signatories is someone who believes that the influenza virus emanates from Venus and is blown to Earth by the solar wind. Collecting a number of signatures from random people cannot be compared to the thoughtful and official decision by the IAU membership.

Will the situation change?

The IAU did not receive sufficiently compelling requests to revisit the issue at the General Assembly in 2009 or 2012 or 2015, and therefore did not schedule any further discussion. Although minor corrections to the language of the resolution may occur at some future IAU General Assembly (e.g., extension to exoplanets), it is unlikely that the outcome of the resolution will change significantly. As the figures above show, it is quite clear that Pluto and Ceres are very different animals than the eight planets. The current classification scheme quite naturally captures this difference, which is a desirable feature of a good taxonomy. One could invent classification schemes in which Pluto and Ceres would belong to the same class as the eight planets, but there are very significant conceptual and implementation problems with such schemes.

What is the next best idea?

Some people have favored a taxonomy in which anything that's "round" is called a planet. There are multiple problems with this:

- For newly discovered objects, roundness is almost never directly observable. We would have to await close-up observations to decide whether the object is a planet or not. A classification scheme that relies on a property that cannot be observed is useless. In contrast, the dynamical dominance criterion adopted by the IAU is one of the easiest to establish for newly discovered objects. (All dynamically dominant bodies are likely to be round, but the reverse is not true).

- How round is round? As opposed to the dynamical criterion described above, there is no clear demarcation between round and non-round objects. There are transition objects, that are sort of round. Would these transition objects be planets or not? If the classification system does not allow for unambiguous classification, it's not a good system.

- The size threshold at which celestial bodies become round depends on many properties, and can vary between roughly 200 and 1200 km. For instance, Mimas (395 km) is round, but Vesta (538 km), a much bigger object, is not round. How would that work? Mimas a planet but Vesta not a planet?

- Many satellites are round, so this taxonomy would eliminate the important distinction between planets and satellites.

Having a label for objects that are round is an interesting idea, however. One proposal is to call anything that's round a "world". Some worlds are planets, others are not. For additional details about this proposal, and suggestions to improve the IAU definition, you can download a presentation I gave in 2009 at the 214th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Pasadena, CA.

Is there a debate about the planet definition?

A few individuals who would like you to believe that there is a substantial debate about the planet definition. What I and others observe are a few dissonant voices in an issue that has been settled by an overwhelming majority. Textbooks have been rewritten, children's books have been rewritten, and it's time to let go.

For further reading

Many years ago David H. Freedman wrote an insightful story that captured may of the relevant arguments. The Atlantic Monthly, Feb 1998, vol. 281, no. 2, p. 22.